Taking a Look at Compression Algorithms

Dissecting various compression algorithms.

Intro

I recently undertook the delusional project of writing my own implementation of a Kafka Broker: MonKafka. Deep into that rabbit hole, I fell into a different one when trying to implement compression for Kafka’s record batches. Kafka supports, as of now, four schemes: GZIP, Snappy, LZ4, and ZSTD. While proceeding with my implementation, I realized I really didn’t know that much about the fascinating topic of compression. I vaguely remembered Huffman trees and some information theory from school, but that was the extent of it. Importing packages and calling friendly APIs felt lacking. So, in the spirit of rabbit holes and indulging, I decided to take a bit of a deep dive to get a better understanding of some of these compression algorithms.

Primer on Compression

What is compression? We represent data using bytes (1 byte = 8 bits). The more bits we have, the more storage space we need and the longer the transmission time. If we can represent some data with fewer bits, we can save on both storage and time it takes to process or transmit. So compression translates to cost savings and better performance. And at scale, we are talking about millions of $.

There are two major types of compression:

- lossless, where no data is lost and the original data can be perfectly reconstructed. In this post, we’ll focus on that.

- lossy, where data is compressed in such a way that the original data cannot be fully recovered, but a close approximation is sufficient. A well-known example is JPEG, which produces an image close enough to the original, and for many cases, this level of quality is acceptable if it gives a better compression ratio.

So, how do we compress data? There are several techniques, some of which you might be familiar with or have heard of:

- Run-Length Encoding (RLE): Consecutive identical elements are replaced with a single element and a count (e.g., “AAAAAA” becomes “6A”).

- Lempel-Ziv (LZ): This method uses back-references to previous sequences. For example,

This is a nice sweet example of LZ, a nice sweet example of LZ.becomesThis is a nice sweet example of LZ, <28, 26>., where <28, 26> means “go back 28 positions and copy 26 characters.” Lempel and Ziv are a big deal in the compression world and their compression scheme LZ77 (created in 1977) is the ancestor of a host of modern schemes such as DEFLATE (gzip) and Snappy. - Huffman Coding: A variable-length encoding algorithm, where symbols have different code lengths (e.g., 10, 110, 1110, etc.), assigns shorter codes to more frequent symbols. In English, for instance,

eis the most frequent letter, andzis one of the least frequent. To save space, we can representewith a short code, while using a longer code forz- which won’t be a significant penalty sincezoccurs less often.

These techniques and others are used in the different schemes with great variations in the implementations.

The various compressions schemes try to optimize three metrics: compression ratio, compression speed and decompression speed.

GZIP

When I started looking into GZIP, it was confusing and frustrating, to say the least. But a lecture by Professor Bill Bird on YouTube not only allowed me to learn so much about the subject and answered all my questions, but it was also very entertaining and fun. I can’t recommend this video and his whole series on compression strongly enough. At some point in the lecture, he was explaining one of the most gnarly pieces of DEFLATE and said:

“…maybe after months and months of working on this scheme with all these bit level hacks they were getting maybe cabin fever or something and um delirium was setting in”

The ‘cabin fever’ comment had me laughing out loud. It came two hours into the intricacies of DEFLATE, and the joke hit the nail on the head!

Anyway, let’s keep going.

Gzip is a file format with a header (10 bytes), footer (8 bytes), and a payload of blocks compressed using the DEFLATE algorithm. It is one of the most famous compression formats in the world. The meat and potatoes of GZIP is DEFLATE.

The DEFLATE algorithm is also used in ZIP,DOCX (Microsoft Word), and PNG (images) files. DEFLATE is everywhere!

DEFLATE Algorithm

The DEFLATE compression algorithm combines LZ77 (technically LZSS, but the RFC refers to it as LZ77) and Huffman encoding:

LZ77: A sliding window algorithm that back-references previous sequences. For example, as mentioned above, “This is a nice sweet example of LZ, a nice sweet example of LZ!” becomes “This is a nice sweet example of LZ, <28, 26>!”, where <28, 26> means “go back 28 positions and copy 26 characters.” We saved quite a bit of characters by replacing them with just two numbers. Imagine doing this multiple times with greater lengths. That is the LZ magic!

Huffman encoding: As explained above, encodes frequent symbol with shorter sequences than less frequent ones, to save space. A simplification of its algorithm is:

- Count the frequencies of symbols.

- Build a binary tree where frequent symbols are closer to the root.

- Traverse the tree to retrieve the symbols.

We create the tree from the bottom-up, combining the least frequent nodes first, ensuring that no path to a leaf overlaps with another. Let’s take a look at an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# In order of most to least frequent: B, A, C, D. B, the most frequent, has the shorter code, thus allowing for the maximum space saving.

/\ Symbol Code

0 1 ------ ----

/ \ A 00

/\ B B 1

0 1 C 011

/ \ D 010

A /\

0 1

/ \

D C

Deflate has the following block types:

- Type 0 (Uncompressed)

- Used when compression provides no benefit, storing data as-is is more efficient. This can be the case for random data or already compressed data.

- Type 1 (Fixed Huffman Codes)

- Uses predefined, fixed Huffman codes i.e. the tree is known beforehand.

- Simpler than type 2 but doesn’t optimize for our data symbol frequencies e.g. unlike the English alphabet where

eis the most common andzthe least, our data might contain mostlyzand a static predefined encoding would be penalizing.

- Type 2 (Dynamic Huffman Codes)

- Builds custom Huffman codes for each block based on symbol frequencies i.e. we account for our data symbol frequencies

- We need compute these codes and include them in the block header, which adds overhead.

In Deflate, there are two distinct Huffman codes

- Literal and backreference length Codes (those are conceptually two different alphabets but merged into the a common one)

- Backreference distance codes

The following quotes from the RFC explains it rather well:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

encoded data blocks in the "deflate" format

consist of sequences of symbols drawn from three conceptually

distinct alphabets: either literal bytes, from the alphabet of

byte values (0..255), or <length, backward distance> pairs,

where the length is drawn from (3..258) and the distance is

drawn from (1..32,768). In fact, the literal and length

alphabets are merged into a single alphabet (0..285), where

values 0..255 represent literal bytes, the value 256 indicates

end-of-block, and values 257..285 represent length codes

(possibly in conjunction with extra bits following the symbol

code) as follows:

Extra Extra Extra

Code Bits Length(s) Code Bits Lengths Code Bits Length(s)

---- ---- ------ ---- ---- ------- ---- ---- -------

257 0 3 267 1 15,16 277 4 67-82

258 0 4 268 1 17,18 278 4 83-98

259 0 5 269 2 19-22 279 4 99-114

260 0 6 270 2 23-26 280 4 115-130

261 0 7 271 2 27-30 281 5 131-162

262 0 8 272 2 31-34 282 5 163-194

263 0 9 273 3 35-42 283 5 195-226

264 0 10 274 3 43-50 284 5 227-257

265 1 11,12 275 3 51-58 285 0 258

266 1 13,14 276 3 59-66

The extra bits should be interpreted as a machine integer

stored with the most-significant bit first, e.g., bits 1110

represent the value 14.

Extra Extra Extra

Code Bits Dist Code Bits Dist Code Bits Distance

---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ------ ---- ---- --------

0 0 1 10 4 33-48 20 9 1025-1536

1 0 2 11 4 49-64 21 9 1537-2048

2 0 3 12 5 65-96 22 10 2049-3072

3 0 4 13 5 97-128 23 10 3073-4096

4 1 5,6 14 6 129-192 24 11 4097-6144

5 1 7,8 15 6 193-256 25 11 6145-8192

6 2 9-12 16 7 257-384 26 12 8193-12288

7 2 13-16 17 7 385-512 27 12 12289-16384

8 3 17-24 18 8 513-768 28 13 16385-24576

9 3 25-32 19 8 769-1024 29 13 24577-32768

To sum up, in a compression block, we have a sequence of literals (uncompressed data) and backreferences (length, distance) pairs.

We know that a length is always followed by a distance. This knowledge allows us to encode the distance symbols using a different Huffman code, since we know where they start. A different code means a shorter one, i.e., more space savings.

Data bytes and lengths are represented together, using the same Huffman code. Data bytes occupy their natural range of 0-255, while lengths, which range from 3 to 258, are represented using codes from 257 to 285. The interesting part is that all 256 possible length values are represented using only 29 symbols. How is this possible? The answer lies in the use of extra bits for less common values.

For example, a length of 30 (second column, fifth row in the first table above) is represented using the code 271 and two extra bits 11.

Why use extra bits? Because some length values are less frequent, they are represented using the same code with additional offset bits. This allows for a more compact representation, even though the extra bits add a small penalty. This approach is similar to how Huffman coding works, where less frequent values are encoded with longer codes to achieve compression efficiency.

The same idea is used for the distance codes. All 32768 possible values are only coding using 30 codes and extra bits. THe bigger distance which are less common are represented with more extra bits as per the table.

For example, a distance of 100 (second column, fourth row tbe second table above) is represented using code 13 and an additional 5 bits, 00011 (3 + 97 = 100).

Suppose we are at the i-th position in our data to be compressed. How do we look for a backreference, i.e., a previous sequence equal to the current one? Do we reexamine all the previous characters? This could be quite CPU-intensive.

The RFC suggests using a chained hash table. This means that all sequences whose first three bytes share the same hash are added to a linked list. When we are at position i, we hash the current 3 bytes and look up the table to find a linked list of all previous sequences that share the same hash and ideally (if no collisions occur) match the current bytes. The presence in the list only means a 3-byte match; we need to extend each one to the largest match possible. How far back into the list we search and when we stop determines the compression level. The further we search for a better match, the more we trade CPU time for a better compression ratio.

Here is how the RFC puts it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

The compressor uses a chained hash table to find duplicated strings,

using a hash function that operates on 3-byte sequences. At any

given point during compression, let XYZ be the next 3 input bytes to

be examined (not necessarily all different, of course). First, the

compressor examines the hash chain for XYZ. If the chain is empty,

the compressor simply writes out X as a literal byte and advances one

byte in the input. If the hash chain is not empty, indicating that

the sequence XYZ (or, if we are unlucky, some other 3 bytes with the

same hash function value) has occurred recently, the compressor

compares all strings on the XYZ hash chain with the actual input data

sequence starting at the current point, and selects the longest

match.

The compressor searches the hash chains starting with the most recent

strings, to favor small distances and thus take advantage of the

Huffman encoding. The hash chains are singly linked. There are no

deletions from the hash chains; the algorithm simply discards matches

that are too old. To avoid a worst-case situation, very long hash

chains are arbitrarily truncated at a certain length, determined by a

run-time parameter.

To improve overall compression, the compressor optionally defers the

selection of matches ("lazy matching"): after a match of length N has

been found, the compressor searches for a longer match starting at

the next input byte. If it finds a longer match, it truncates the

previous match to a length of one (thus producing a single literal

byte) and then emits the longer match. Otherwise, it emits the

original match, and, as described above, advances N bytes before

continuing.

Run-time parameters also control this "lazy match" procedure. If

compression ratio is most important, the compressor attempts a

complete second search regardless of the length of the first match.

In the normal case, if the current match is "long enough", the

compressor reduces the search for a longer match, thus speeding up

the process. If speed is most important, the compressor inserts new

strings in the hash table only when no match was found, or when the

match is not "too long". This degrades the compression ratio but

saves time since there are both fewer insertions and fewer searches.

Golang Deflate implementation

Let’s get into the weeds—the fun part. In no particular order, we will take a look at some parts of the code which is rather significant. This is just to give a tiny taste.

In Golang’s implementation of Deflate, the literals and backreferences are represented as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

literalType = 0 << 30

matchType = 1 << 30

type token uint32

// Convert a literal into a literal token.

func literalToken(literal uint32) token { return token(literalType + literal) }

// Convert a < xlength, xoffset > pair into a match token.

func matchToken(xlength uint32, xoffset uint32) token {

return token(matchType + xlength<<lengthShift + xoffset)

}

So they are represented as a token. A huffmanBitWriter will take a list of these tokens and encodes based on its type and the Huffman code.

The package uses a neat and simple Hash function to construct the hash table of previous potential back refs

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

const hashmul = 0x1e35a7bd

// hash4 returns a hash representation of the first 4 bytes

// of the supplied slice.

// The caller must ensure that len(b) >= 4.

func hash4(b []byte) uint32 {

return ((uint32(b[3]) | uint32(b[2])<<8 | uint32(b[1])<<16 | uint32(b[0])<<24) * hashmul) >> (32 - hashBits)

}

Multiplying by a constant (hashmul) helps spread out the bits of the hash value, improving the “randomness” of the result. 0x1e35a7bd has been chosen because it likely reduces the risk of collisions, possibly based on empirical testing. The right shift by 32 - hashBits ensures our hash consists of only hashBits, which is 17 in the implementation.

The chained hash table is defined within the compressor struct as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Input hash chains

// hashHead[hashValue] contains the largest inputIndex with the specified hash value

// If hashHead[hashValue] is within the current window, then

// hashPrev[hashHead[hashValue] & windowMask] contains the previous index

// with the same hash value.

chainHead int

hashHead [hashSize]uint32

hashPrev [windowSize]uint32

When we loop over our data, we hash the next 4 bytes (not 3 as the RFC suggest), then we update the hash table:

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Update the hash

hash := hash4(d.window[d.index : d.index+`minmatch`Length])

hh := &d.hashHead[hash&hashMask]

d.chainHead = int(*hh)

d.hashPrev[d.index&windowMask] = uint32(d.chainHead)

*hh = uint32(d.index + d.hashOffset)

hh is the index of the previous sequence with the same hash, i.e., the previous sequence that starts with the same 4 bytes. It marks the start of a chain of sequences that also share the same hash (start with the same bytes). Based on the compression level, we try to find the best match by traversing the chain of sequences that share the same hash.

Here are the supported compression levels:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

type compressionLevel struct {

level, good, lazy, nice, chain, fastSkipHashing int

}

var levels = []compressionLevel{

{0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}, // NoCompression.

{1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}, // BestSpeed uses a custom algorithm; see deflatefast.go.

// For levels 2-3 we don't bother trying with lazy matches.

{2, 4, 0, 16, 8, 5},

{3, 4, 0, 32, 32, 6},

// Levels 4-9 use increasingly more lazy matching

// and increasingly stringent conditions for "good enough".

{4, 4, 4, 16, 16, skipNever},

{5, 8, 16, 32, 32, skipNever},

{6, 8, 16, 128, 128, skipNever},

{7, 8, 32, 128, 256, skipNever},

{8, 32, 128, 258, 1024, skipNever},

{9, 32, 258, 258, 4096, skipNever},

}

THe default is 6. {6, 8, 16, 128, 128, skipNever},. In the FindMatch function, to look for a match in the chained hash table we can find :

1

2

3

4

5

// We quit when we get a match that's at least nice long

nice := len(win) - pos

if d.nice < nice {

nice = d.nice

}

You might notice how for fast compression levels, we accept a match of 16 or 32 in length, but for higher levels, where we willingly sacrifice speed for a better compression ratio, we go up to 258 (the max per the Deflate RFC). The default is 128.

The next lines in FindMatch are also quite intersting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

// If we've got a match that's good enough, only look in 1/4 the chain.

tries := d.chain

length = prevLength

if length >= d.good {

tries >>= 2

}

This is a great tradeoff. If our current match is good enough (which is 8 for the default level and 32 for the highest compression level), let’s not waste too much time and reduce our search space by 4 (shifting twice to the right >>= 2, equivalent to dividing by four). The number of tries is d.chain, which is determined by the compression level. The higher the level, the greater the number of tries.

A simplified look at the main loop inside FindMatch.:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

for i := prevHead; tries > 0; tries-- {

if wEnd == win[i+length] {

n := matchLen(win[i:], wPos, `minmatch`Look)

if n > length {

length = n

offset = pos - i

if n >= nice {

// The match is good enough that we don't try to find a better one.

break

}

wEnd = win[pos+n]

}

}

i = int(d.hashPrev[i&windowMask]) - d.hashOffset

}

matchLen finds the maximum number of matching bytes between our current sequence and one of the sequences that share the same hash for the first 4 bytes. Then, we loop trying to find a better match. i = int(d.hashPrev[i & windowMask]) - d.hashOffset moves us to the next sequence in the chain. We stop when we either exceed the nice length or exhaust our tries. length and offset are the tuple of the backreference we are looking for.

This, in my opinion, is the heart of our compression algorithm—the search for a backref. This implementation is a sight for sore eyes. It’s enjoyable to look at such elegant code.

This is barely scratching the surface of this package. There’s a lot more going on, especially with the Huffman code. But let’s stop here before getting too lost.

Snappy

Snappy is also a proud descendant of the LZ family. It focuses heavily on speed, and according to the GitHub repo of the official Google implementation, it compresses at about 250 MB/sec or more and decompresses at about 500 MB/sec or more. This is an order of magnitude faster than the fastest mode of zlib. Its compression ratios are typically between 1.5-1.7x for plain text, and about 2-4x for HTML. These are lower than the ratios achieved by zlib (DEFLATE), which are 2.6-2.8x for plain text, and 3-7x for HTML, according to the benchmark in the README.

Snappy was previously called “Zippy.” This made me think of Bertha and Alan from Two and a Half Men—what a show!

Anyway, here’s a rather nice description of the Snappy format from the Golang implementation repo:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Each encoded block begins with the varint-encoded length of the decoded data,

followed by a sequence of chunks. Chunks begin and end on byte boundaries.

The first byte of each chunk is broken into its 2 least and 6 most significant bits

called l and m: l ranges in [0, 4) and m ranges in [0, 64). l is the chunk tag.

Zero means a literal tag. All other values mean a copy tag.

For literal tags:

- If m < 60, the next 1 + m bytes are literal bytes.

- Otherwise, let n be the little-endian unsigned integer denoted by the next

m - 59 bytes. The next 1 + n bytes after that are literal bytes.

For copy tags, length bytes are copied from `offset` bytes ago, in the style of

Lempel-Ziv compression algorithms. In particular:

- For l == 1, the offset ranges in [0, 1<<11) and the length in [4, 12).

The length is 4 + the low 3 bits of m. The high 3 bits of m form bits 8-10

of the offset. The next byte is bits 0-7 of the offset.

- For l == 2, the offset ranges in [0, 1<<16) and the length in [1, 65).

The length is 1 + m. The offset is the little-endian unsigned integer

denoted by the next 2 bytes.

Each block (up to 64k) is composed of the following chunks, determined by the 2 least significant bits of the first chunk byte:

00: Literal byte, i.e., no compression.- If the literal’s length is < 60, the 6 most significant bits of the first byte are used to encode it. Then, the data bytes follow.

- For lengths 60, 61, 62, and 63, these 6 bits represent the number of bytes used to encode the length:

- 60 => 1 byte,

- 61 => 2 bytes,

- etc.,

followed by the data bytes after the length bytes.

01: LZ compression with back references, going up to 2048 (1«11) bytes back, and a length in [4,12].

It is interesting how bits are economically used to represent the length (3 bits are enough since only 8 values are possible in [4,12]) and 11 bits for the offset: 3 most significant bits in the first byte + the second byte (8 + 3 = 11).10: LZ compression with back references, going up to 65536 (1«16) bytes back, and a length in [1,65].

The length is determined by the 6 most significant bits in the first byte, and the offset by the next two bytes.11: A legacy chunk type that is no longer used.

Here is the implementation of the first chunk type: literal. It’s quite nifty:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

// emitLiteral writes a literal chunk and returns the number of bytes written.

//

// It assumes that:

// dst is long enough to hold the encoded bytes

// 1 <= len(lit) && len(lit) <= 65536

func emitLiteral(dst, lit []byte) int {

i, n := 0, uint(len(lit)-1)

switch {

case n < 60:

// length fits in the 6 most significant bits of the first byte

dst[0] = uint8(n)<<2 | tagLiteral

i = 1 // we used only one byte before the data

case n < 1<<8: // n < 256

// length < 256, it fits on the next byte

dst[0] = 60<<2 | tagLiteral

dst[1] = uint8(n)

i = 2 // we used 2 bytes before the data

default:

// we assume length <= 65536 and we know length > 256, so two bytes to encode the length

dst[0] = 61<<2 | tagLiteral

// we are writing in little endian (least-significant byte at the smallest address.)

dst[1] = uint8(n) // least significant 8 bits of n

dst[2] = uint8(n >> 8) // shit right by 8 => most significant 8 bits of n

i = 3 // we used 3 bytes before the data

}

return i + copy(dst[i:], lit) // copy the actual data

}

The comments inside the function are added by your truly.

Here are the two lines required to write chunk type 1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

func emitCopy(dst []byte, offset, length int) int {

// logic for chunk types 2 omitted ...

// type 1 (tagCopy1 =0x01)

// first byte

// 3 most significant bits: are the 3 most significant bits of the offset 8-11)

// 3 next bits: length - 4 (length is < 12)

// 2 last bits are 01 which are chunk type 1

dst[i+0] = uint8(offset>>8)<<5 | uint8(length-4)<<2 | tagCopy1

// second byte: least significant 8 bits of the 11 bit offset

dst[i+1] = uint8(offset)

return i + 2

}

Here is the main Snappy loop simplified:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

// encodeBlock encodes a non-empty src to a guaranteed-large-enough dst. It

// assumes that the varint-encoded length of the decompressed bytes has already

// been written.

//

// It also assumes that:

// len(dst) >= MaxEncodedLen(len(src)) &&

// minNonLiteralBlockSize <= len(src) && len(src) <= maxBlockSize and maxBlockSize == 65536.

func encodeBlock(dst, src []byte) (d int) {

maxTableSize = 1 << 14

var table [maxTableSize]uint16

// The encoded form must start with a literal, as there are no previous

// bytes to copy, so we start looking for hash matches at s == 1.

s := 1

nextHash := hash(load32(src, s), shift)

for {

nextS := s

candidate := 0

for {

s = nextS

nextS = s + bytesBetweenHashLookups // Writer's note: bytesBetweenHashLookups is 1 but It can grow by 1 every 32 misses

candidate = int(table[nextHash&tableMask])

table[nextHash&tableMask] = uint16(s)

nextHash = hash(load32(src, nextS), shift)

if load32(src, s) == load32(src, candidate) {

break

}

}

// A 4-byte match has been found. We'll later see if more than 4 bytes

// match. But, prior to the match, src[nextEmit:s] are unmatched. Emit

// them as literal bytes.

d += emitLiteral(dst[d:], src[nextEmit:s])

for {

// Invariant: we have a 4-byte match at s, and no need to emit any

// literal bytes prior to s.

base := s

// Extend the 4-byte match as long as possible.

//

// This is an inlined version of:

// extend match: keep going as long as previous seq == current seq

s += 4

for i := candidate + 4; s < len(src) && src[i] == src[s]; i, s = i+1, s+1 {

}

d += emitCopy(dst[d:], base-candidate, s-base)

}

}

}

I omitted some optimization code, but this is the gist of Snappy, and it is refreshingly simple. We hash 4 bytes at a time and only keep 1 previous reference, unlike DEFLATE, which keeps a whole chain. Once we find a match—a hash of 4 previous bytes that match our 4 current bytes — we exit the first nested for loop. We then emitLiteral, meaning we write the literal bytes before the match where no match was found, then keep extending our current match to get the biggest backreference possible. We emit the backreference using emitCopy and keep going until we reach the end of our src.

This is somewhat of an oversimplification, but this is the gist of it!

The difference between Snappy and DEFLATE in searching for previous back references is:

- Match length: 64 for Snappy and 258 for DEFLATE.

- Snappy contents itself with the most recent match, i.e., the most recent sequence that starts with the same 4 bytes, whereas DEFLATE maintains a list of entries that share the same prefix.

So, DEFLATE sacrifices space and time to find a better match, and I believe this is the major reason for the speed difference.

LZ4

LZ4 is quite similar to Snappy. They were both released in 2011. They are both part of the LZ family. LZ4 is however faster in both compression and decompression and offers similar compression ratios compared to Snappy.

Here is a benchmark copied from LZ4’s Github repository:

The benchmark uses lzbench, from @inikep compiled with GCC v8.2.0 on Linux 64-bits (Ubuntu 4.18.0-17). The reference system uses a Core i7-9700K CPU @ 4.9GHz (w/ turbo boost). Benchmark evaluates the compression of reference [Silesia Corpus] in single-thread mode. lzbench: https://github.com/inikep/lzbench [Silesia Corpus]: http://sun.aei.polsl.pl/~sdeor/index.php?page=silesia

| Compressor | Ratio | Compression | Decompression |

|---|---|---|---|

| memcpy | 1.000 | 13700 MB/s | 13700 MB/s |

| LZ4 default (v1.9.0) | 2.101 | 780 MB/s | 4970 MB/s |

| LZO 2.09 | 2.108 | 670 MB/s | 860 MB/s |

| QuickLZ 1.5.0 | 2.238 | 575 MB/s | 780 MB/s |

| Snappy 1.1.4 | 2.091 | 565 MB/s | 1950 MB/s |

| [Zstandard] 1.4.0 -1 | 2.883 | 515 MB/s | 1380 MB/s |

| LZF v3.6 | 2.073 | 415 MB/s | 910 MB/s |

| [zlib] deflate 1.2.11 -1 | 2.730 | 100 MB/s | 415 MB/s |

| LZ4 HC -9 (v1.9.0) | 2.721 | 41 MB/s | 4900 MB/s |

| [zlib] deflate 1.2.11 -6 | 3.099 | 36 MB/s | 445 MB/s |

The ratios are similar between Snappy and LZ4, with Snappy achieving around 2.1 and LZ4 offering a compression speed of 780 MB/s, which is faster than Snappy’s 565 MB/s. These are impressive numbers when you think about it. We’re talking about compression speeds approaching 1 GB/s on a single machine, with decompression speeds exceeding that. One can see how compression can play a pivotal role in data applications. We can reduce our data size by half at very impressive speeds.

The LZ4 frame format looks as follows:

| MagicNb | F. Descriptor | Data Block | (…) | EndMark | C. Checksum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 bytes | 3-15 bytes | 4 bytes | 0-4 bytes |

The most interesting parts are the Frame Descriptor and Data Blocks. The Descriptor contains flags about the version, whether blocks have their own checksum, the maximum block size (64KB up to 4 MB), etc.

Let’s note that LZ4 doesn’t use CRC32 for the checksum but an algorithm called xxHash.

Another important observation is that LZ4 has a streaming mode on which backreferences span multiple blocks. i.e. block N can backreference a literal from block N-1.

The Data blocks are as follows:

| Block Size | data | (Block Checksum) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 bytes | 0 - 4 bytes |

If the most significant bit is 1, the block is uncompressed. If it is 0, the real fun begins.

Here is an abridged, slightly modified quote from the block format description:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

An LZ4 compressed block is composed of sequences. A sequence is a suite of not-compressed bytes, followed by a match copy operation.

Each sequence starts with a token. The token is a one byte value, separated into two 4-bits fields. Therefore each field ranges from 0 to 15.

The first field uses the 4 high-bits of the token. It provides the length of literals to follow.

The value 15 is a special case: more bytes are required to indicate the full length. Each additional byte then represents a value from 0 to 255, which is added to the previous value to produce a total length. When the byte value is 255, another byte must be read and added, and so on. There can be any number of bytes of value 255 following token.

...

A literal length of 280 will be represented as :

15 : value for the 4-bits High field

255 : following byte is maxed, since 280-15 >= 255

10 : (=280 - 15 - 255) remaining length to reach 280

Following token and optional length bytes, are the literals themselves. They are exactly as numerous as just decoded (length of literals). Reminder: it's possible that there are zero literals.

Following the literals is the match copy operation.

It starts by the offset value. This is a 2 bytes value, in little endian format (the 1st byte is the "low" byte, the 2nd one is the "high" byte).

The offset represents the position of the match to be copied from the past. For example, 1 means "current position - 1 byte". The maximum offset value is 65535.

Then the `matchlength` can be extracted. For this, we use the second token field, the low 4-bits. Such a value, obviously, ranges from 0 to 15. However here, 0 means that the copy operation is minimal. The minimum length of a match is 4. As a consequence, a 0 value means 4 bytes. Similarly to literal length, any value smaller than 15 represents a length, to which 4 must be added, thus ranging from 4 to 18. A value of 15 is special, meaning 19+ bytes, to which one must read additional bytes, one at a time, with each byte value ranging from 0 to 255. ... There is no limit to the number of optional 255 bytes that can be present.

LZ4’s approach is quite interesting. The literal and match (copy) blocks are combined, and the token is used to indicate the length of both. The 4 high bits represent the length of the literal, while the 4 low bits represent the length of the match. If the length exceeds what can be stored in 4 bits, additional bytes are used. Each extra byte can encode a length of up to 255. Thus, two extra bytes can represent lengths up to 510 instead of 16k if read as a uint16. I assume in practice lengths rarely exceed the extra two bytes limit. This is a rather intriguing way of handling things.

Offsets are handled with 2 simple little-endian bytes, which naturally limits the sliding window to 65535.

The main loop to compress a block share quite a bit of common ground with Snappy. We rely on a hash table to look to backreference.

Here is an abridged version from a neat Golang implementation with some additional comments:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

func (c *Compressor) CompressBlock(src, dst []byte) (int, error) {

// Zero out reused table to avoid non-deterministic output (issue #65).

c.reset()

// Return 0, nil only if the destination buffer size is < CompressBlockBound.

isNotCompressible := len(dst) < CompressBlockBound(len(src))

// adaptSkipLog sets how quickly the compressor begins skipping blocks when data is incompressible.

// This significantly speeds up incompressible data and usually has very small impact on compression.

// bytes to skip = 1 + (bytes since last match >> adaptSkipLog)

const adaptSkipLog = 7

// si: Current position of the search.

// anchor: Position of the current literals.

var si, di, anchor int

sn := len(src) - mfLimit

if sn <= 0 {

goto lastLiterals

}

// Fast scan strategy: the hash table only stores the last 4 bytes sequences.

for si < sn {

// Hash the next 6 bytes (sequence)...

match := binary.LittleEndian.Uint64(src[si:])

h := blockHash(match)

h2 := blockHash(match >> 8)

// We check a match at s, s+1 and s+2 and pick the first one we get.

// Checking 3 only requires us to load the source one.

ref := c.get(h, si)

ref2 := c.get(h2, si+1)

c.put(h, si)

c.put(h2, si+1)

offset := si - ref

if offset <= 0 || offset >= winSize || uint32(match) != binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(src[ref:]) {

// No match. Start calculating another hash.

// The processor can usually do this out-of-order.

h = blockHash(match >> 16)

ref3 := c.get(h, si+2)

// Check the second match at si+1

si += 1

offset = si - ref2

if offset <= 0 || offset >= winSize || uint32(match>>8) != binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(src[ref2:]) {

// No match. Check the third match at si+2

si += 1

offset = si - ref3

c.put(h, si)

if offset <= 0 || offset >= winSize || uint32(match>>16) != binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(src[ref3:]) {

// Skip one extra byte (at si+3) before we check 3 matches again.

si += 2 + (si-anchor)>>adaptSkipLog

continue

}

}

}

// Match found.

lLen := si - anchor // Literal length.

// We already matched 4 bytes.

mLen := 4

// Extend backwards if we can, reducing literals.

tOff := si - offset - 1

for lLen > 0 && tOff >= 0 && src[si-1] == src[tOff] {

si--

tOff--

lLen--

mLen++

}

// Add the match length, so we continue search at the end.

// Use mLen to store the offset base.

si, mLen = si+mLen, si+minMatch

// Find the longest match by looking by batches of 8 bytes.

for si+8 <= sn {

// let's remember that X XOR X = 0 => we read 8 bytes at time from the current position and

// the potential backreference and xor them to compare equality. Cool!

x := binary.LittleEndian.Uint64(src[si:]) ^ binary.LittleEndian.Uint64(src[si-offset:])

if x == 0 {

si += 8

} else {

// TrailingZeros64 gives the number of 0 bit on the right i.e. bits that match.

// The encoding is little endian so the bits of the right are the ones that come at the lower memory address.

// By shifting >> 3 we are dividing by 8 i.e. counting the num of matching bytes

si += bits.TrailingZeros64(x) >> 3

break

}

}

mLen = si - mLen

if di >= len(dst) {

return 0, lz4errors.ErrInvalidSourceShortBuffer

}

// if the match is < 15, we put it in the low 4 bit of `token`

if mLen < 0xF {

dst[di] = byte(mLen)

} else {

// we put 15 in the lowest 4 bits of `token`. The remainder of mlen will be added in 255 increments bellow

dst[di] = 0xF

}

// Encode literals length.

if lLen < 0xF {

dst[di] |= byte(lLen << 4) // as described above, 4 high bits represent the literal's length

} else {

// literal length > 15, keep adding bytes, each of which represents 255

// (15 + ... + 255 + ... + remainder_less_than_255)

dst[di] |= 0xF0

di++

l := lLen - 0xF

for ; l >= 0xFF && di < len(dst); l -= 0xFF {

dst[di] = 0xFF

di++

}

if di >= len(dst) {

return 0, lz4errors.ErrInvalidSourceShortBuffer

}

dst[di] = byte(l)

}

di++

// Literals.

copy(dst[di:di+lLen], src[anchor:anchor+lLen])

di += lLen + 2

anchor = si

// Encode offset.

if di > len(dst) {

return 0, lz4errors.ErrInvalidSourceShortBuffer

}

dst[di-2], dst[di-1] = byte(offset), byte(offset>>8)

// Encode match length part 2 in 255 increments

if mLen >= 0xF {

for mLen -= 0xF; mLen >= 0xFF && di < len(dst); mLen -= 0xFF {

dst[di] = 0xFF

di++

}

if di >= len(dst) {

return 0, lz4errors.ErrInvalidSourceShortBuffer

}

dst[di] = byte(mLen)

di++

}

// omitted ..

}

}

Some observations:

- For each pass, three hashes

s,s+1, ands+2are computed and checked. This speeds things up. - On match, we extend the length backwards and forward with an elegant XOR comparison.

- LZ4 lends itself well to binary operations, and I am guessing this is why it is so fast.

- The gist of the algorithm is quite similar to Snappy’s, so it is interesting to see how small variations can have a considerable impact on performance.

There is a variation of LZ4 called LZ4_HC (High Compression), which trades customizable CPU time for compression ratio, as per lz4.org. Behind the scenes, it extends the hash table by adding a chain (much like Deflate) and introduces a new compression level parameter that indicates how deep the chain we can look to find a better match, i.e., how much CPU we can trade for a better match and thus a higher compression ratio! It is remarkable how it all boils down to this.

Once again, this is just a glimpse into LZ4, but I hope it gives you a good sense of its functionality.

ZSTD

ZSTD (Zstandard) is the successor to LZ4. It was developed by the same author, Yann Collet, and released in 2016. Here’s a cool video of him answering questions about ZSTD.

ZSTD is quite impressive. Why? Because it offers compression ratios similar to or better than Deflate, while achieving speeds comparable to LZ4 and Snappy.

Here is a benchmark from the official repo:

For reference, several fast compression algorithms were tested and compared on a desktop featuring a Core i7-9700K CPU @ 4.9GHz and running Ubuntu 20.04 (

Linux ubu20 5.15.0-101-generic), using lzbench, an open-source in-memory benchmark by @inikep compiled with gcc 9.4.0, on the Silesia compression corpus.

| Compressor name | Ratio | Compression | Decompress. |

|---|---|---|---|

| zstd 1.5.6 -1 | 2.887 | 510 MB/s | 1580 MB/s |

| [zlib] 1.2.11 -1 | 2.743 | 95 MB/s | 400 MB/s |

| brotli 1.0.9 -0 | 2.702 | 395 MB/s | 430 MB/s |

| zstd 1.5.6 –fast=1 | 2.437 | 545 MB/s | 1890 MB/s |

| zstd 1.5.6 –fast=3 | 2.239 | 650 MB/s | 2000 MB/s |

| quicklz 1.5.0 -1 | 2.238 | 525 MB/s | 750 MB/s |

| lzo1x 2.10 -1 | 2.106 | 650 MB/s | 825 MB/s |

| [lz4] 1.9.4 | 2.101 | 700 MB/s | 4000 MB/s |

| lzf 3.6 -1 | 2.077 | 420 MB/s | 830 MB/s |

| snappy 1.1.9 | 2.073 | 530 MB/s | 1660 MB/s |

~2.9 ratio for 510MB/s compression and 1.5GB decompression. This is what I call having the best of both worlds!

ZSTD is more complex compared to the previous algorithms, and explaining it in detail would be too ambitious for the scope of this blog post. However, it felt wrong to stop here, so I’ll briefly touch on some of the ideas it builds on.

ZSTD is still an LZ-based scheme, but it incorporates Huffman encoding, FSE (more on that below), and several clever tricks. FSE is based on a method derived from arithmetic coding.

In the remaining sections, I’ll try to provide a gentle introduction to some of these blocks.

Arithmetic Coding

Huffman coding allows us to represent frequent symbols with fewer bits. If e is the most frequent symbol in the English alphabet, it makes sense that it would get the shortest bit representation, i.e., just one bit (0 or 1).

The problem with Huffman is that we need an integer number of bits to represent a symbol. Consider the sequence eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeb. Here, e has a probability of 98%, and b has a probability of 2%. Given Huffman’s nature, the shortest code would be just 1 bit. However, because of this, both e and b end up being encoded with the same 1-bit representation.

Ideally, there should be a proportional relationship between probability and the number of bits used to represent a symbol.

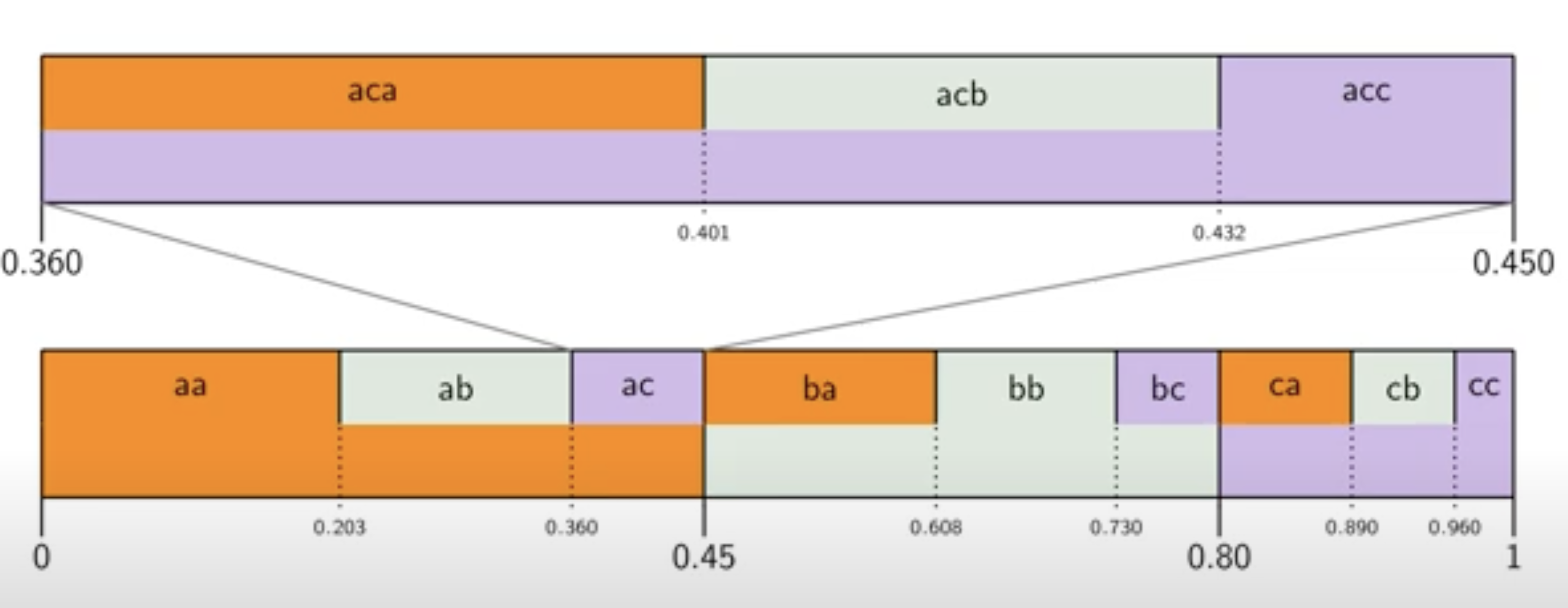

Arithmetic coding attempts to solve this issue. The idea is quite elegant. Imagine we have the a sequence with letter a, b, and c , with probabilities of a, b, and c being 0.45, 0.35, and 0.2, respectively. To represent a, we can send any value in the interval [0, 0.45) (with 0.45 not included). For b and c, we use the intervals [0.45, 0.8) and [0.8, 1), respectively.

For the second character, we subdivide the first interval according to the same probabilities. If the first character is a, we can send a value from the subintervals [0, 0.203), [0.203, 0.36), and [0.36, 0.45) to represent a, b, and c, respectively. Here, 0.203 is 0.45 times 0.45, and 0.36 is 0.35 (the probability of b) times 0.45, added to 0.203.

In simple terms, we divide the interval [0, 1] according to the probabilities of the symbols. After encoding each symbol, we subdivide its interval according to the remaining probabilities, and we continue subdividing for each subsequent symbol. The final compressed result is simply a value within the correct interval representing our sequence.

The example and the following neat representation are borrowed from this tremendous lecture by the same professor mentioned above:

At the third step, once we have encoded ac, the interval is expanded and subdivided according to the probabilities. The entire interval now represents the sequence ac, but each subinterval corresponds to one of the next possible values. So, if the next value is a, resulting in the sequence aca, we need to pick from the first subinterval for a, the second for b, and the third for c.

You might think that this technique is impractical for encoding long sequences, as the interval keeps getting smaller, potentially leading to a fractional part with hundreds, thousands, or even millions of bits. This is, of course, impossible to handle because computers can only work with a limited precision. While it might be possible to represent a number with a million digits in its fractional part using clever techniques (such as a linked list), it would be highly impractical.

So, what’s the point of arithmetic coding? Have we been wasting our time with it? Luckily, no. There are renormalization techniques that truncate our numbers while ensuring correctness. This allows us to always operate within 16, 32, or 64 bits.

FSE: Finite State Entropy

Arithmetic encoding requires a lot of multiplication, rounding, and division at the symbol level, making it CPU-intensive-unlike Huffman encoding. This makes arithmetic encoding impractical for large amounts of data.

ZSTD uses a technique called Finite State Encoding, based on Asymmetric Numeral Systems, which builds on the ideas of arithmetic encoding but offers better computational efficiency.

FSE and ANS are quite involved and complex. For the brave of heart, the author of ANS has a YouTube video explaining it. Here is also a blog post by none other than Yann, the creator of ZSTD, introducing FSE.

Trainable Dictionaries

One very cool feature of ZSTD is the ability to train dictionaries from a set of files. Dictionaries are simply common patterns, keywords, or other repetitive sequences found in the files. The compressor then looks up matches from these dictionaries instead of using backreferences.

Quote from the Github repository:

1

2

3

4

zstd offers dictionary compression, which greatly improves efficiency on small files and messages.

It's possible to train zstd with a set of samples, the result of which is saved into a file called a dictionary.

Then, during compression and decompression, reference the same dictionary, using command -D dictionaryFileName.

Compression of small files similar to the sample set will be greatly improved.

So if we are compressing a specific kind of data say some form of log files, we can train a dictionary and hit the ground running using it.

Conclusion

Compression is truly a fascinating field. It’s about stripping data of redundancies, reducing entropy, and extracting information. One interesting idea is that, at their core, AI models are nothing more than compression models that take the corpus of data humanity has and boil it down to a set of weights.